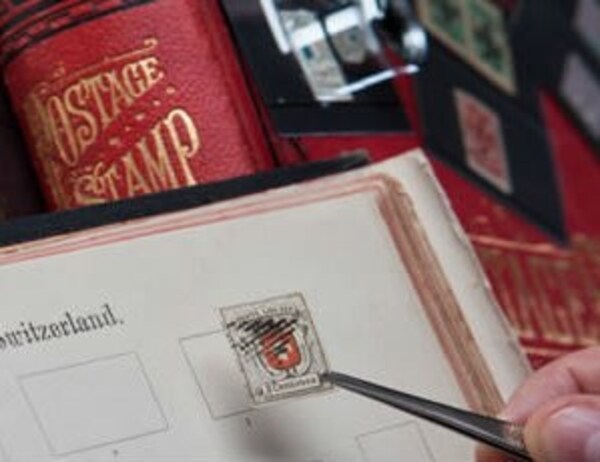

Many years ago the late Sir John Marriott, Keeper of the Royal Collection, told me that he was collecting the first stamp of each country. His aim eventually was to possess singles, mint and fine used, as well as examples on cover. This ambition had developed from an early interest in the Penny Black. After all, it was surely every serious collector's desire to possess at least one specimen of the world's first adhesive postage stamp. Back in the 1960s when he embarked on this project it was a relatively easy matter to get good, four-margined Penny Blacks, at least from the commoner plates, without either undue expense or trouble.

When I later asked him how his quest was progressing he complained that British dealers either did not have what he was looking for, or expected him to pay well over the odds. This was back in the time when it was customary to buy material at a discount off the Gibbons catalogue prices, and while this may have worked quite well with British stamps, he found that European or Latin American stamps of comparable vintage were much more expensive.

That it is a situation which has steadily got worse with the passage of the years. It is not that Continental material has really become more expensive in relation to British stamps of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, but rather that these British stamps are undervalued by comparison.

Various reasons are usually advanced by way of explanation. One obvious one is the relative volume of available material. To be sure, the Penny Black may be the world's first stamp but it is by no means a rarity. With a print run totalling 73 millions, even if only five per cent have survived in collectable condition we are still talking in terms of over three million stamps - and there are probably few special stamps of the present day that are produced in such astronomical editions.

On the other hand, such is the number of philatelists who would not consider their collection complete without at least a token example of the Penny Black, that demand would always race far ahead of the supply. Well, that might have been true at one time, though I doubt it. When I began collecting stamps - more years ago now than I care to admit - you could purchase a reasonable, three-margined example for under a pound. For a fiver, however, you would have got a really nice specimen. I am talking about the late 1940s, a time when the average wage of a workingman was about £10 or less, so this will give you some idea of relative worth. Applying this principle to Penny Blacks at the present time you will find that it would take the average manual worker a lot less than half a week to earn the money that would purchase a good Penny Black.

When we examine the situation in regard to the classic stamps of other countries, however, we find that prices have shot through the roof. In general good quality European stamps, for example, have risen more sharply over the past half century, indeed, in many cases quite dramatically. Perhaps they were previously undervalued in relation to British material, but more often the reason for the sharp increase has been economic. This was particularly true in Germany, a country with a very strong philatelic tradition but which had experienced tremendous socio-economic upheavals.

This is not the whole story for another factor which has come into play in recent years has been the economic changes which have taken place in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe in the past decade alone. The rise of a new entrepreneurial middle class has greatly stimulated interest in the philately of these countries and their neighbours, with a consequent upsurge of market values. Add to this the emergence of very buoyant philatelic markets in countries where little or no philatelic interest existed (notably China in the last dozen years, although this is also true of other Far Eastern countries like Japan, Korea, Thailand and Singapore) and one can begin to understand why 'foreign' stamps in general have forged ahead.

Of course, this is a gross over-simplification, and we should not lose sight of the fact that philately is a global hobby and that British stamps have a strong following everywhere. It's just that the demand for good quality foreign stamps exceeds the supply to a greater degree than applies in British stamps.

In fact, although the Line-engraveds have always commanded the greatest attention and are regarded as the blue chips of British philately, the Surface-printed stamps are, in many cases, much more elusive, especially if you are seeking only top-quality material. Apart from the much-vaunted Abnormals, there are many other stamps in this range which are extremely hard to find in really fine condition and which are undervalued. How often does the 2 shillings brown of 1880 (currently listed by Gibbons at £8,000 mint and £1,700 used) turn up in the saleroom? To my mind this is a prime example of a very rare stamp whose current market value does not truly reflect this.

Perhaps the reason that good quality Victorian British stamps are undervalued relative to their European counterparts is that, from a purely superficial viewpoint, the Victorian series seems rather monotonous. It is only when you scratch the surface of the subject and master the intricacies of the De La Rue stamps, with their subtle changes from no corner letters, to uncoloured letters, first small and later large, and then the large coloured letters from 1873 onwards, that you begin to appreciate their charm. Add the complexities of plate numbers and watermarks and you have a series with endless potential. In the comparable period (1855-90) European stamps probably underwent more frequent changes of design. Remember also the sweeping political changes that witnessed the demise of the German and Italian states which have yielded so many of the very expensive stamps of the present time.

One thing becomes abundantly clear and that is that although good quality Victorian stamps are relatively undervalued this situation is unlikely to continue much longer. Already dealers all over Britain are reporting a marked increase of interest in British stamps and more people taking up stamp-collecting or coming back into the hobby. This phenomenon may be explained by the current economic situation. Interest rates are at an all-time low which means that savers have far less incentive to keep their money in the bank or tied up in stocks and shares which have performed so poorly in the past three years. Suddenly stamps are looking a lot more attractive, but one very encouraging trend is that people are buying stamps not so much for investment but for the pure enjoyment of them. This is a much healthier situation than existed in 1979 when a great deal of money was pumped into philately when it was heavily promote as an 'alternative investment'. The present situation is much more stable, and points to a steady rise in values which will surely redress the balance between British and Continental material in the foreseeable future.

This trend is already quite apparent in British stamps of the Georgian and early Elizabethan periods which have hardened considerably in the past few months alone after languishing in the doldrums. And if past performance is anything to go by, it can only be a matter of time before the new intake of serious collectors turns its attention to the Edwardian and Victorian periods as well.

General

General

General

General

General

General