Although Adolf Hitler's Thousand Year Reich lasted only twelve years, the fascination for the darkest era in modern European history is as strong as ever, as reflected in such prime-time television programmes as 'Hitler's Henchmen', the re-run of 'The World at War' and seemingly inexhaustible documentaries about the Holocaust. Yet the manner in which a bunch of thugs and gangsters so totally seduced a highly civilised country remains one of the greatest enigmas of all time.

How could the nation of Goethe and Beethoven have fallen for the man with that ridiculous moustache and dreadful accent? How did this leader of a Fred Karno's army of malcontents, ignominiously defeated in the streets of Munich when they tried to stage a coup, end up less than ten years later as the democratically elected Chancellor of Germany?

We may never know the answer, for Hitler's rise to power has been endlessly studied and debated; but an extraordinary collection documenting life and times during the Nazi era which recently came to light, and which will be offered as a single lot in a forthcoming sale at Sandafayre, vividly conveys the atmosphere of the 1920s and 1930s.

Here are such mute reminders of the Nazis as the enamelled party lapel badge and the red, white and black swastika arm-band, mounted alongside a sketch by Hitler (who was a skilled draughtsman with ambitions to become a great artist) of a Party storm trooper, showing the swastika emblems on his helmet and banner. There are mementoes from various extreme right-wing groups, such as the Thule Society, including a postcard bearing its emblem (out of which evolved the swastika) and signed by its members on 9 December 1922.

The Sturm Abteliung (storm detachment) or SA to which the storm troopers belonged, started as a paramilitary force, designed to keep order at Party meetings and demonstrations, and protect Hitler and his henchmen from attack by the Communists. The SA gained its first recruits from the Freikorps, nationalist freebooters who fought the Poles in Silesia and the Danes in Slesvig just after World War I when the German Empire was disintegrating.

These roughnecks and bully boys were in danger of giving the infant National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) a bad name, but in 1921 Hitler entrusted Captain Franz Pfeffer von Salomon with the task of licking them into shape and creating a disciplined force. He created the Nazi salute and organised the first rallies at Nuremberg. Pfeffer, a Prussian and a non-Nazi who had been much-decorated for distinguished service in the war, was dismissed by Hitler in 1930 and replaced by his old company commander, Ernst Röhm. This turned out to be a good career move for Pfeffer, who thereafter dropped out of the picture. Four years later, when there was a show-down between the SS and the SA, it was Röhm and his associates who were summarily executed in what came to be known as the 'Night of the Long Knives'.

This collection contains some excellent mementoes of the man who first rejoiced in the title of Oberste SA Führer (Supreme SA Leader) or OSAF for short, including one of a series of excellent photographs by Hoffmann showing party leaders and ceremonies, such as early party rallies. Another shows Hitler formally handing over the bloodstained Nazi flag which had been carried during the November 1923 Putsch to the up-and-coming Heinrich Himmler, boss of the Schutzstaffel ('protection squad'). Originally a small part of the SA, the main function of the SS in its early years was to act as messenger-boys for the Party bosses and to sell the Nazi newspapers on street corners, but Himmler soon transformed it into the Party's elite police force. It separated from the SA in 1930 and soon became its deadliest rival.

A particularly fascinating aspect of this collection is the manner in which the Nazi Party metamorphosed from a disorganised rabble of the unemployed, ex-soldiers and criminal elements into the ruthlessly efficient machine which first conquered Germany and then set out to conquer the world. You look at the sepia photographs in this collection, showing Hitler and his pals in their brownshirts and shorts like a bunch of overgrown Boy Scouts, and wonder how anybody ever took them seriously. The tragedy for Germany and the world, of course, is that so many people regarded them as the saviours of their country.

The rituals and ceremonies are reflected in the badges and insignia, the labels and stickers, the leaflets and pamphlets that set out Nazi philosophy and race hatred or articulated the grievances that were the bitter legacy of the Versailles Treaty.

These mute reminders of the Nazi rise to power and their subsequent conduct during the Third Reich speak louder than words. A Nazi 'charity' label sold in the streets at 10 pfennig bears the slogan 'Aryan blood the highest good' while a large sticker on the back of an envelope of 1941 lashes out at Jews, blacks and the French with equal vehemence. There are electioneering pamphlets and party propaganda postcards from the turbulent years of 1930-32 when the Weimar republic was sliding into anarchy; you begin to realise how society was polarised between the Communists and the Nazis and the latter probably seemed at the time the lesser of two evils.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles Germany was not permitted an air force, but the Nazis got round this by creating gliding schools where young men learned the rudiments of flying in the National Socialist Flying Corps which made much of the fact that aviation was 'just a sport'. The collection includes a ticket to a Flying Corps demonstration, followed by dinner and dance, in April 1937.

The later material in this extraordinary collection covers the period of World War II itself. There is 'A Last Appeal to Peace', a transcript of a speech by Hitler on 19 April 1940 which was dropped as a propaganda leaflet by the Luftwaffe over England, while a leaflet dropped on American forces during the Battle of the Bulge subtly stirred up resentment at the 'fat cats' back in the USA lining their pockets at the expense of the GIs. By contrast, a Christmas card from a soldier on the Eastern Front is a poignant memento of the campaign that ultimately destroyed Nazi Germany

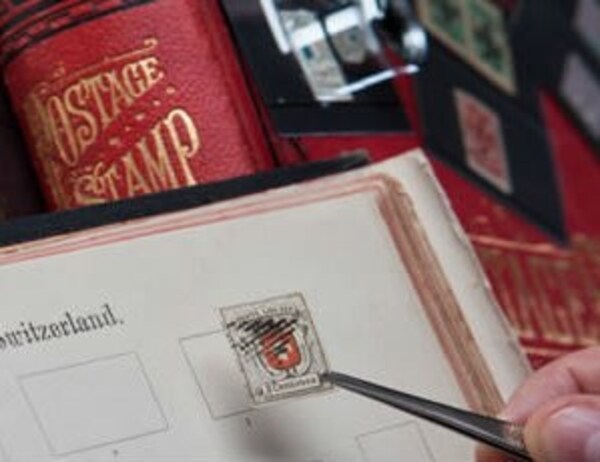

There are grim mementoes of the Waffen SS, the vast army that eventually incorporated men from many countries (including the English prisoners of war who served in the Britannia Legion). There are stamps, labels and leaflets of the Legion Wallonie, for example, which recruited young Belgians to fight under Leon Degrelle on the Eastern front.

There are stamps, labels and postcards (including the very rare Serbian cards) with anti-Jewish and anti-masonic propaganda. A yellow star cloth patch worn by Dutch Jews is mounted alongside a photograph of a Rabbi reciting the prayer for the dead over the corpses of fellow Jews, while a group of German soldiers look on with expressions of disinterest, boredom or amusement on their faces - their reaction being more horrific than the pile of bodies.

The most chilling items of all, however, are seemingly innocuous covers sent through the post in Germany. It is only when you notice the cachets inscribed 'Schalter aufgeliefert' (shown at the window) that you realise they were sent to or from Jews. Such letters had to be taken to a special counter at the post office for examination before they were censored and sealed. Thus a petty postal regulation became one of the minor irritations that, bit by bit, would escalate in humiliation and persecution and lead inexorably towards Hitler's Final Solution.

General

General

General

General

General

General